News

Get to Know a Flow Feature: Vortices

It’s time once again to get to know a flow feature! This time we take a look at the vortex, a spinning structure that delivers a lot of power in a compact package. Mysterious and menacing, the vortex is the Tyrannosaurus rex of coherent flow structures.

First of all, let’s get the polar vortex out of the way. You’ve no doubt heard of the polar vortex. We’ve ALL heard of the polar vortex, and frankly, it’s getting old. CPP’s meteorologists have been telling polar vortex jokes on their lunch breaks for decades. Then, in 2014, the media got hold of it, turned it into a hashtag, and suddenly everyone was an expert on high-latitude tropospheric cyclones. Let me tell you, we were rocking vortices around here long before they became cool. Or, more accurately, incredibly cold.

But we digress…

A vortex is nothing more than a region of fluid that swirls about a central axis. It can develop in a liquid like water, as when you pull the plug in a bathtub, or it can develop in air, as when a tornado reaches down from the sky. Tropical cyclones (hurricanes and typhoons) are vortices, as is the Great Red Spot on the planet Jupiter, an anticyclonic storm that has been raging for hundreds of years or more, frustrating generations of Jovians who just want to get a little sun.

Vortices are coherent structures, which means they are neither completely random nor merely transient phenomena. They persist over a relatively long period of time compared with the bulk flow, they possess predictable and recognizable shapes, and they exhibit identifiable physical properties. Pressure in a vortex, for example, increases with distance from the center, and vortices possess measurable angular momentum, which is the tendency for something that spins to continue spinning.

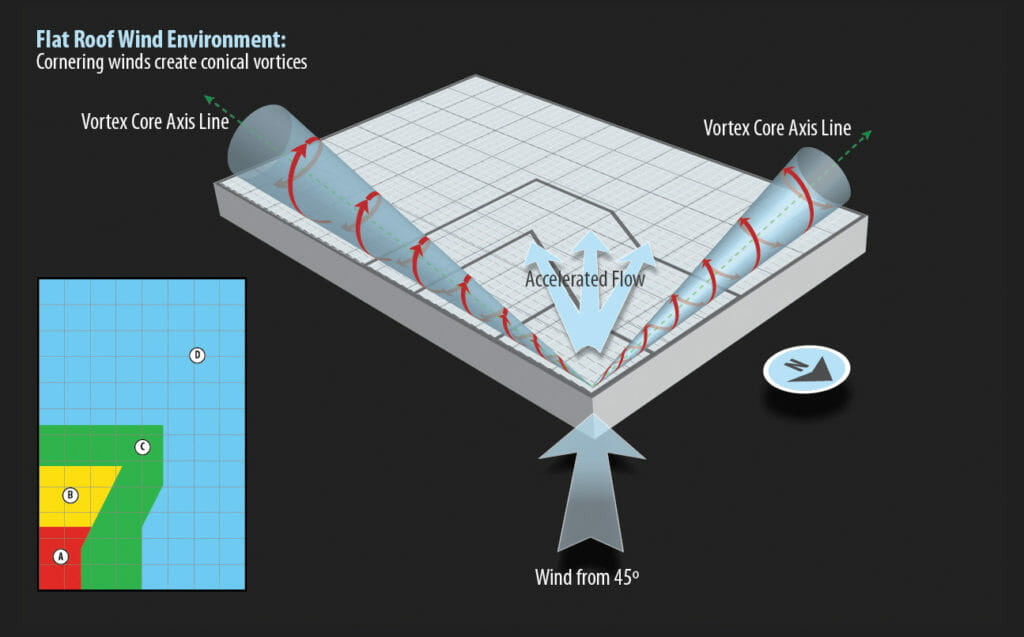

In a wind engineering context, the term vortex almost always refers to the tornado-like swirling structure that develops when air has to turn a sharp corner. These corner vortices create incredible suction, which is why we have vortices to thank for the additional bolstering required at roof corners. They’ve even been known to push rooftop concrete pavers into little piles.

Aeronautical engineers use this power to their advantage. The leading edge extensions found on fighter jets like the F/A-18—plus many other variations on delta wings including Concorde—encourage vortex development, which creates upper surface suction at high angles of attack, enhancing lift.

If you come to visit us at CPP (and we hope you do), we’ll show you around the wind tunnel, and more than likely, you’ll get to see a vortex in action. And you might even get to meet Dr. David Banks, a Principal at CPP who also happens to be a renowned expert on the topic of corner vortices, which were the subject of his dissertation. Apparently, perusing a PhD was a great way to learn more about the topic (as well as treat mild cases of insomnia).

So there you have it. Far from just a fun word to say, the vortex is a complex yet compelling part of the natural environment and, if you design your building the right way, not necessarily part of the built environment.